Inland Empire: Pleasures and Horrors of the Poor Image

Unpublished

May 13, 2022

May 13, 2022

“When you have a poor image, there’s lots more room to dream.”

— David Lynch, quoted in interview with Variety.

As a teenager, I inherited a collection of VHS tapes of horror movies my school were getting rid of as they made the switch from video to DVD.[i] Watched in my room on my family’s tiny old TV — they, too, had made the switch to digital — films like Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982), The Hunger (Tony Scott, 1983), and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (David Lynch, 1992) thrilled and terrified me. Revisiting these films in the years since, either in cinemas or at home on Blu-ray disks, I’ve now seen these films as they are “supposed” to be seen by the standards of any cinephile — in high resolution versions, without the “imperfections” of the lower-quality video format. The latter viewings afforded a newfound clarity: I could better appreciate the films’ craft, I could make out every detail in a scene. I could, in short, see more — so why did it feel like something was missing? Clearly, it wasn’t just the content of the films themselves that made such an impression on my teenage self, but also the material qualities of the analogue video format: its grainy images, its faded colours and fuzzy lines. These VHS tapes were worn out, in some moments unclear almost beyond the point of comprehension; the few that had been recorded from television broadcasts were even worse (fig 1.). Rather than take away from my viewing experience, these material traces added to the unease, the claustrophobia, the sense of illicitness that was already occurring in these horror films. What I had discovered seeing these films in higher resolution was the affective qualities of the less-than-perfect, what Lucas Hilderbrand terms the “bootleg aesthetics” of video and what Hito Steyerl calls, in reference to the internet age, the “poor image.” The link between image resolution and affectual response became especially clear to me when I saw David Lynch’s 2006 film Inland Empire on DVD. Shot on the MiniDV tape format at a resolution that was, even at the time of production, far below the industry standard, this was a film that actively chose to embrace visual “imperfection,” medium-specific noise, a low-quality image.

My goal here is not to “resolve” Inland Empire, an 180-minute-long experimental feature film whose complex, web-like narrative structure has led many writers to compare to networked culture or the hyperlink itself. Rather, I want to show that Inland Empire is a remarkably prescient film with regard to the ambivalent status of the poor image in contemporary society — especially in its unique affective capacities. If the film’s grainy DV (digital video) images encourage a more participatory kind of viewing related to what Laura Marks calls “haptic visuality” in reference to the sensual appeal of video’s materiality, I want to demonstrate that they also carry the potential to engender a sense of unease, playing on the associative and inherent horror of the poor image. Specifically, I link this to live-feed surveillance aesthetics and anxieties surrounding the rise of mass surveillance. Finally, I want to consider the strange case of Inland Empire’s “remastering,” and how this new, “improved” version highlights the film’s own circulation as a poor image — one that enlightens my own viewing by suggesting the return of the artwork’s “aura” in the age of mass circulation.[ii]

Figure 1: Stills from Twin Peaks: Fire

Walk With Me,

comparing frames taken from a HD streaming version (left) and my own VHS copy

(right), showing cropping, loss of detail, damage to video, inability to render

contrast.

Figure 1: Stills from Twin Peaks: Fire

Walk With Me,

comparing frames taken from a HD streaming version (left) and my own VHS copy

(right), showing cropping, loss of detail, damage to video, inability to render

contrast.

POOR IMAGES, HAPTIC VISUALITY

Ours is an image world in high definition. We record and view our images in 2K, 4K, even 8K resolution. They are sharp, polished, perfect. Or at least, that’s the idea being sold to us. In actual fact, contemporary society is awash with images that are of decidedly substandard definition — digital images that have been copied, compressed, edited beyond recognition. Such images are the preoccupation of Hito Steyerl’s essay “In Defence of the Poor Image,” which probes the political assumptions underlying the supposedly universal adoption and adoration for the “rich” image at the expense of its lowly offspring. “Poor images are poor,” she writes, “because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images […] their lack of resolution attests to their appropriation and displacement” (38). The language of oppression that Steyerl uses to describe the poor image (they are, in a nod to Fanon, “the contemporary Wretched of the Screen”) is not entirely figurative; discussing the fetishized role 35mm film continues to play for the cinema, she notes that the obsession with the medium’s clarity (as supposedly non-ideological) obscures the role it plays in economies of film production and distribution that are “often conservative in their very structure” (35).

Steyerl’s argument recalls those put forward in 1970s Latin America in favour of a Third Cinema. In their celebrated manifesto, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino clarify that the “35mm camera, 24 frames per second, arc lights, and a commercial place of exhibition for audiences were conceived not to gratuitously transmit any ideology, but to satisfy […] a specific world-view: that of US financial capital” (51). Thus, an anti-capitalist, decolonial Third Cinema would, for Julio García Espinosa, necessarily would be an “imperfect” cinema. Despite their promise to disrupt hierarchies of the image, however, the alternative audiovisual economies facilitated by the proliferation of the poor image in the digital age have not fulfilled their promise quite as anticipated: “the real and contemporary imperfect cinema,” Steyerl writes, is “much more ambivalent and affective,” encompassing “[h]ate speech, spam, and other rubbish” (40). This “ambivalent and affective” quality of the poor image, as well as its tendency towards the illicit, is discussed by Lucas Hilderbrand in reference to a slightly earlier period, that of analogue video. Contrary to the dominant narrative that we crave ever-increasingly high-quality images, Hilderbrand notes the widespread enthusiasm for the “bootleg aesthetics” of pirated video — the “white noise, the jittery image, the unnatural colors, the grain, the momentary loss of signal” that suggest its illegitimate circulation (65). In enabling us to come into contact with the image in its materiality, these “imperfections” engender an emotional response: intrigue, elation, or uneasiness, as I discovered as a teenager.

Evidently, the poor image has unique affective capacities that the privileged “perfect” image does not, which might give us some idea of why the artist might appropriate it. For theorist Laura Marks, writing in 2002, the video work of artists including Seoungho Cho, Tran T. Kim-Trang, Shauna Beharry and Sadie Benning is suggestive of a “haptic visuality” because of the sense of touch conveyed by the material qualities of video. This trend of artists eschewing the more clear, “perfect” medium of film in favour of low-res video might “express a cultural dissatisfaction with the limits of visuality”; importantly, it responds to this dissatisfaction by enlisting the erotics of the haptic to what is conventionally considered an optical medium (4). Thus, the extremely lo-res, colourless Pixelvision (a Fisher-Price toy camera) format favoured by Benning functions as “an ideal haptic medium” whose eroticism lies in “its incompleteness, the inability ever to see all, because it’s so grainy, its chiaroscuro so harsh, its figures mere suggestions” (Marks 10-11).

Though Marks does not explore it, such a description is also suggestive of the eeriness of the poor image. Peggy Ahwesh’s horror short Nocturne (1998) and Michael Almereyda’s feature-length Nadja (1994), the latter a vampire movie produced by David Lynch, both make use of Pixelvision inserts that exploit the camera’s frustration of clarity, its capacity for horror as well as seduction. Theorist Shane Denson finds a similar approach in commercial horror cinema’s appropriation of what he calls the “discorrelated images” of the digital age, those screen artifacts that again call attention to their own materiality. Films of the “found footage” or “desktop horror” subgenres mediate and exploit anxieties surrounding the poor image by incorporating the aesthetics of home video, webcam, surveillance apparatus, webpage glitch, and social media into their narrative and aesthetic substance. As such, “post-cinematic horror trades centrally on a slippage between diegesis and medium; the fear that is channelled through moving-image media is in part also a fear of (or evoked by) these media” (Denson 154). In films like The Blair Witch Project (1999), Paranormal Activity (2007) and Unfriended (2014), the film we are watching is also the film that has been discovered, or is in the process of being created, within the narrative diegesis. As we shall see, the blurring of diegesis and medium becomes a central issue in Inland Empire, where the aesthetics of surveillance seem to infect the narrative logic of the film itself.

“THE MIND CAN GO DREAMING…”

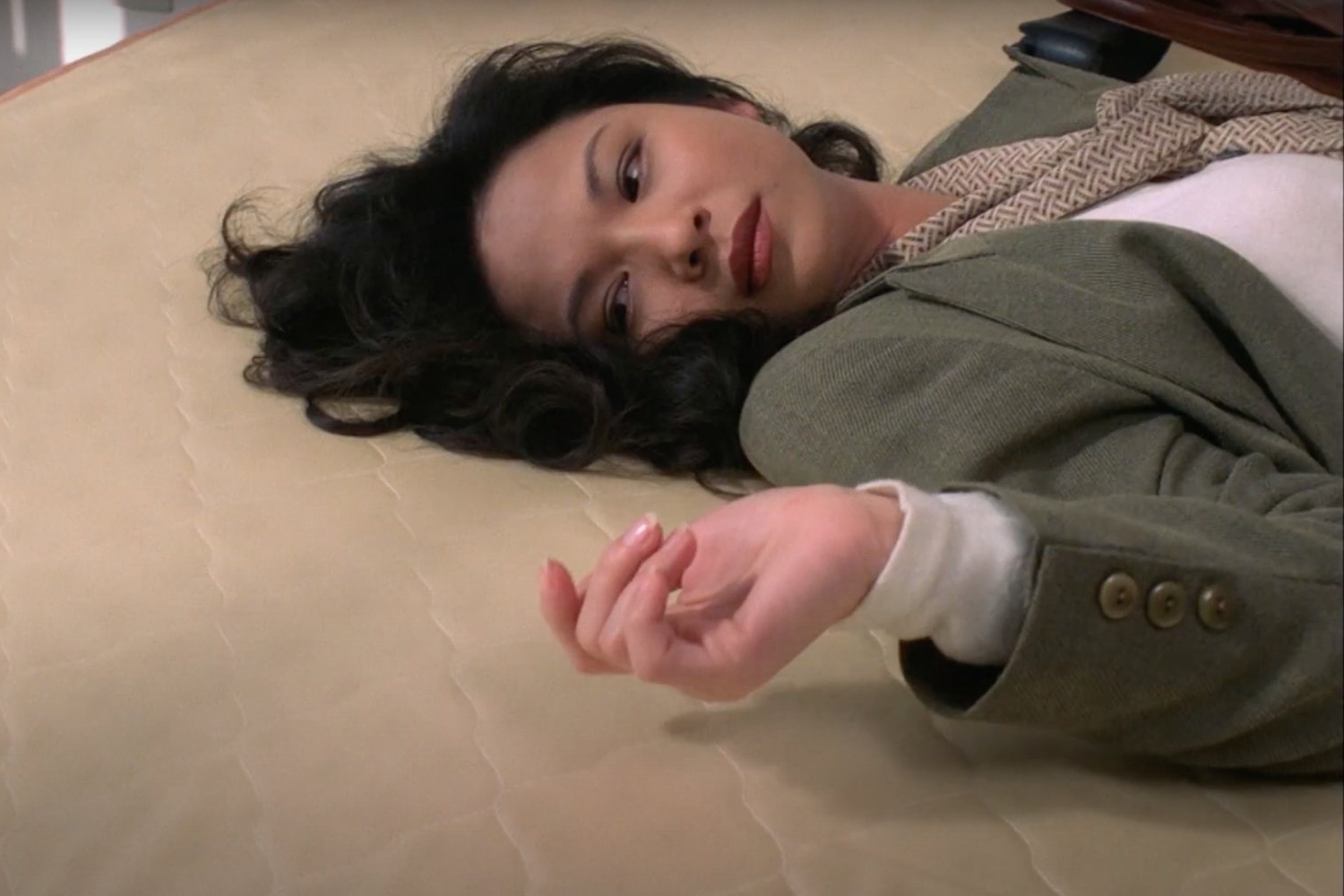

Inland Empire’s plot centres on aspiring actress Nikki Grace (Laura Dern), who is playing the lead (“Susan Blue”) in a Hollywood film called On High in Blue Tomorrows, a remake of a supposedly cursed Polish melodrama that was never finished because its stars were murdered. As distinctions collapse between Nikki’s life, the role she is playing, and the life of the murdered Polish actress (as well as the corresponding “Sue” role shewas playing), levels of narrative reality become so thoroughly confused as to become essentially meaningless. Numerous critics have likened the film’s structure to the logic of the hyperlink, a comparison that strikes me as particularly apt in capturing the film’s positioning at the precipice between cinema and post-cinema.[iii] It is through this metaphor that we can begin to think of Inland Empire as being about modes of recording and viewing in the digital age.

Consider the film’s opening. Inland Empire begins with a few seconds of black screen suddenly pierced by beam of light coming from what appears to be an old-school film projector, and which illuminates the title. The next shot is an extreme close up of a record player, with flickering light dancing over the grooves of a record. A muffled announcer introduces “Axxon N. The longest running radio play in history. Tonight, continuing in the Baltic region, a grey winter day in an old hotel…” And just like that, we’re in what appears to be a hotel, where a crying woman (Karolina Gruszka, credited as “The Lost Girl”) sits on a bed; the image is overlaid with a shot of what appears to be the lens of an analogue camera. The woman is watching a television, which eventually begins to play something resembling a low-budget television sitcom (complete with canned laughter) starring three humanoid rabbits, and then our introduction to Dern’s character Nikki. The implication is that the woman is watching the images that comprise the film Inland Empire on a screen, and therefore some sort of framing device — though this will be violently dispelled by the film’s end. We will return later to Lynch’s metacinematic techniques and problematising of narrative diegesis, but for now it’s sufficient to note that, at the film’s outset, we’re immediately confronted with not only a mixture of genres and forms — the projected film, the record, the radio play, the television sitcom[iv] — but also with the technologies of the audiovisual. Inescapable, then, is our engagement with the technology used to make the film itself: Inland Empire was shot on a camcorder at a definition far lower than what is expected of a film made for cinematic release, as is immediately apparent.

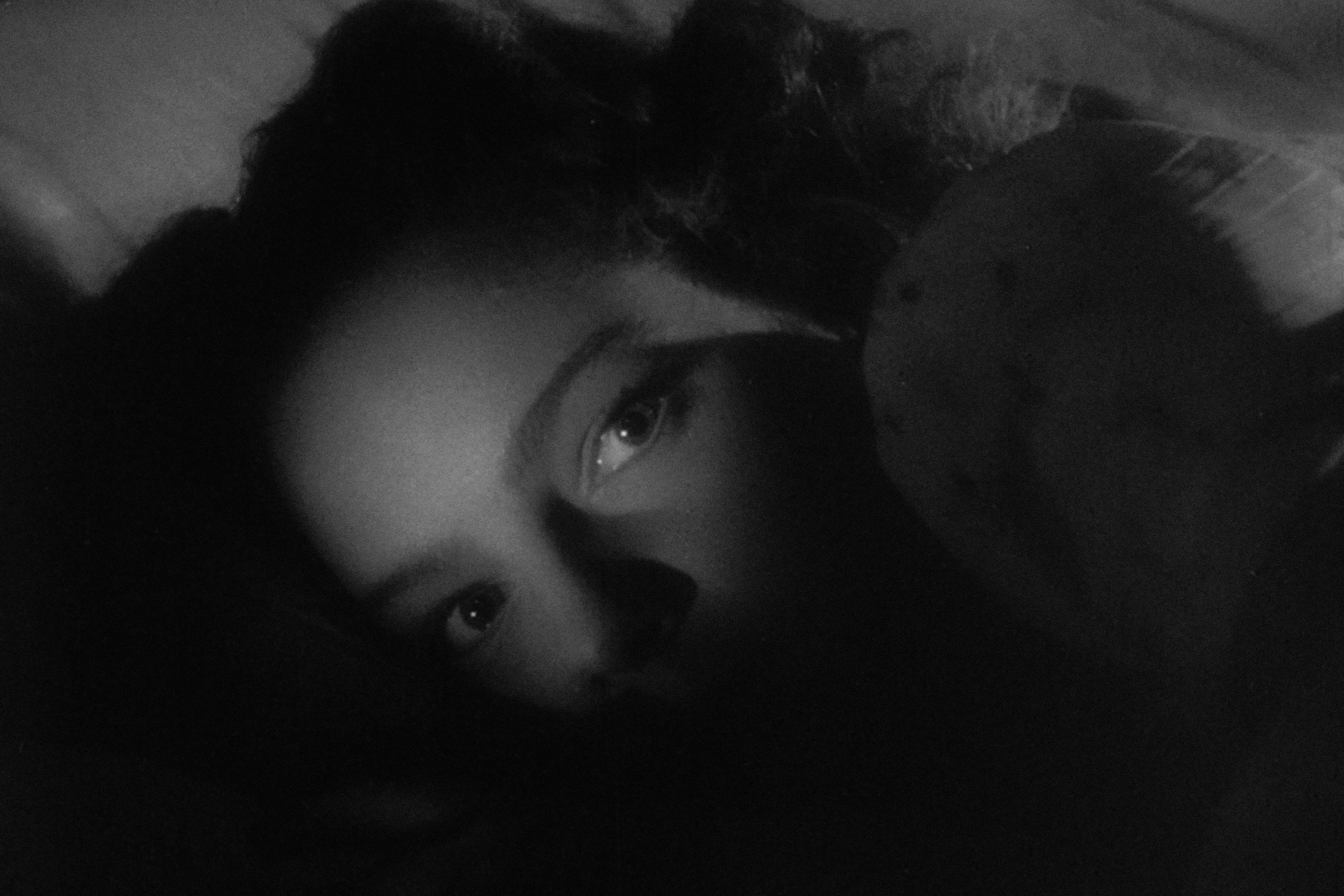

Why opt for a low-quality image? In artists’ video we see plenty of so-called poor images, but such an approach is far less common for such images to reach the cinema, what Steyerl terms the “flagship store” in “the class society of images” (33). Lynch’s film was not without precedent; the turn of the millennium saw certain relatively high-profile filmmakers experimenting with DV as it first became available, including Spike Lee (Bamboozled), Agnès Varda (The Gleaner’s and I), Pedro Costa (In Vanda’s Room), and Lars von Trier (Dancer in the Dark; all 2000).[v] By 2006, the year Inland Empire was released, features by George Lucas, Alexander Sokurov, Robert Rodriguez, Jia Zhangke, Miranda July had all been shot on high-definition digital using a 24-frame system. What is interesting to note is that, while these filmmakers were negotiating a trade-off between emulating the traditional medium of film and leaning into an as-yet-undefined digital cinematic look, Lynch refused even the most basic simulations of photochemical film recording — the Sony DSR-PD150 does not shoot in high definition nor at the standard frame rate. As Amy Taubin writes in her review of the film, “[t]he PD-150 produces images that look like nothing but video. The visuals in Inland Empire look as if they're decomposing before your eyes” (57). Indeed, its images are grainy, unstable, and depthless in a manner suggestive of the haptic qualities that encourage engagement with video image as image. Lynch’s cinematography and lighting choices emphasise these qualities: the colour range is muted, details are lost to shadow, highlights are often blown out (fig. 2).

Figure 2: Stills from Inland Empire.

Figure 2: Stills from Inland Empire.

Lynch’s own reasoning behind his “love” for the Sony PD150 clarifies what might be gained when visual information is lost: “sometimes, in a frame, if there’s some question about what you’re seeing, or some dark corner, the mind can go dreaming. If everything is crystal clear in that frame […] that’s all it is” (153). The idea that the poor image requires some level of imagination (to “fill in” the pro-filmic information supposedly lost) suggests a more participatory role for viewer that recalls Mark’s notion of haptic viewing:

It puts into question cinema’s illusion of representing reality, by pushing the viewer’s look back to the surface of the image. And it enables an embodied perception, the viewer responding to the video as to another body and to the screen as another skin. (Marks 4)

Whereas the artists Marks surveys conceive of this as an erotic encounter, Lynch milks this “skin-to-skin” contact for the weird and the eerie affects it is able to produce. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is a terrifying deployment of digital image manipulation. The image occurs in the scene in which Nikki confronts the “Phantom” who she shoots and whose face is overlaid with a hideously warped version of Nikki’s own likeness (fig. 3). By the standards of its contemporary CGI, the effect has a slapdash quality, reminiscent of poorly Photoshopped memes that were beginning to circulate the internet in the period. The image, however, is so uncanny precisely because it refuses to even attempt a sense of depth; the illusion of three-dimensional screen space collapses into two dimensions, and again our look is pushed to the surface of the image.

Figure 3: Stills from Inland Empire.

SURVEILLANCE AESTHETICS

Aside from the specific look of Inland Empire, we can say that more broadly Lynch’s low-definition video evokes the aesthetics of the underground film, the home movie, the sex tape.[vi] It plays on the idea that images we’re meant to watch are high quality, and that low-quality images belong to the domain of either that beyond the law, as with the illegal bootleg, or are the property of the law itself, as with surveillance footage. Indeed, the first characters we see in the film are shot in black, from high angles, and with blurred faces, strongly suggesting video surveillance. For Anne Jerslev, Lynch’s repeated use of wide-angle long shots contributes to the lingering sense of surveillance that permeates the film (7). In the film’s closing stages this is made all the more explicit when Nikki unexpectedly turns to look into the camera, seemingly breaking the fourth wall, and we cut to the hotel room where the Lost Girl is watching a television playing the very same image of Nikki we have just seen (fig. 4). Nikki then enters a movie theatre, where she sees herself being projected in real-time onto the screen. Finally, Nikki enters the hotel room and embraces the Lost Girl; playing on the live-feed television screen is a long shot of the room that encompasses the television which, in a weird instance of mise en abyme, plays Nikki’s entrance (fig. 5). Combined, these scenes give the impression that the film Inland Empire has entered into its own narrative diegesis, with its filmmaker’s images becoming surveillance footage. Here we can see that Inland Empire is tapping into similar anxieties about collapse of medium and diegesis — where does the narrative space begin and end? — that Denson finds in the contemporaneous horror cinema of discorrelated images.

Figure 4: Stills from Inland Empire.

Within the film’s narrative, who controls the images on the monitor? Who is doing the surveilling, and for what purpose? Such questions, unsurprisingly never answered, suggest Inland Empire as a particularly canny film about surveillance in the digital age, our inability to know who or what is looking at us at all times and why. As Steyerl notes, the ubiquity of the camera — especially since the availability of mobile phones with cameras in the mid-2000s — has “created a zone of mutual mass surveillance […] On top of institutional surveillance, people are now also routinely surveilling each other by taking countless pictures and publishing them in almost real time” (167).[vii] Inland Empire’s production began just a few years after 9/11, one of the major domestic consequences of which was the expansion of mass surveillance as part of the Patriot Act, including the PRISM surveillance program. Perhaps it would not be too much of a stretch to suggest that Lynch’s choice of a camera that produces supposedly sub-standard images, closer to home video than the hi-def “perfection” of the classical cinema, metacinematically plays on the horror of ubiquitous surveillance: the technology that liberates Lynch’s filmmaking — cheaper production costs, longer takes, automatic focus, and so on — is the same technology that turns every public building, lamppost, ATM, and laptop into a potential tool of the surveillance state. This might be another way to approach what Steyerl identifies as the profound ambivalence of the poor image and its apparatus.

RE-MASTERING THE POOR IMAGE

Though I have discussed the sense of unreality that the lo-res images of Inland Empire take on — their flatness, their oneiric qualities that invite participation — I am wary of repeating the traditional marketing line that claims that quests to improve audiovisual quality will achieve increasingly more “realistic” cinema. High-resolution, especially in excess, is perfectly capable of creating its own sense of unreality.[viii] In the past, Lynch himself has bemoaned the “crystal clear” quality of HD: “I saw a piece of film on the screen in my mixing room shot in high-def; it was some kind of science fiction” (Lynch 153). This might be best explained in terms of what Laura Mulvey terms, with reference to the photographic work of Jeff Wall, as the “technological uncanny […] that is, a sense of uncertainty when confronted by a phenomenon that can actually be easily explained by the use of a new and unfamiliar technology” (Mulvey 30). Anyone who saw Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy (2012-2014) — shot and projected in cinemas at a hyperreal 48 frames per second — will have some sense of what this means. So too will anyone who has seen Jackson’s documentaries They Shall Not Grow Old (2018) or The Beatles: Get Back (2021) which both made use of AI technologies to increase the frame rate of archive footage and upscale it to 4K: the combined effect is one of simultaneous smoothening and sharpening of the image that has a particularly uncanny quality.[ix]

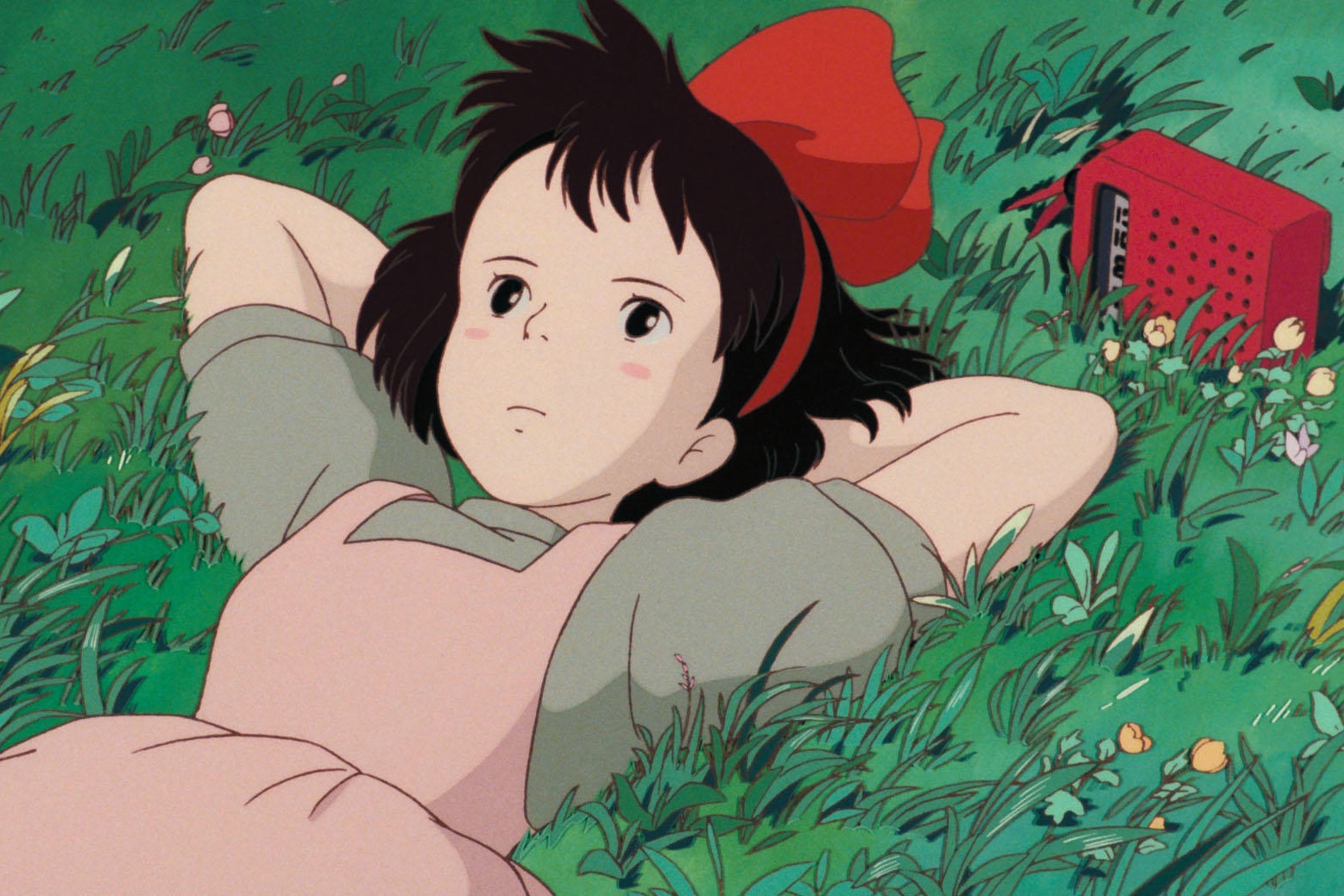

As I write this, Inland Empire is currently playing American cinemas on re-release in the form of a “remastered” version. But how exactly do you “remaster” a film shot on DV in standard definition to meet the demands of a market obsessed with clarity? The process Lynch’s team undertook was characteristically idiosyncratic: the original film, which had been output to HDCAM-SR tape, was downscaled back to SD, then upscaled to 4K using Topaz Labs’ Gigapixel AI software.[x] Finally, a layer of artificial film grain was added. The resulting version sees the pixelated quality of the original DV footage competing with the alternately sharp and smeary look of the AI upscale as it attempts to “fill in the blanks” (fig. 6). In an interview to coincide with the film’s original release, Lynch was quoted as celebrating the SD look of his film: “When you have a poor image, there’s lots more room to dream” (Dawtrey). In interviews to accompany the re-release a decade and a half later, however, Lynch can be found celebrating the ability of AI technology to reverse some of those key qualities of video I have previously been describing. The remaster, he claims, “gives it more depth and color and focus and makes it look much more beautiful, much more cinematic” (Hemphill). Elsewhere, Lynch admits to becoming “depressed” with the DVD version of the film, the way the “plastic” look of the video skin, with its “tendency to kind of keep calling attention to itself,” constituted a barrier to audience engagement; “Now I think it’s easier to go into that world” (Simon).

Figure 5: Still from Inland Empire, comparing a frame taken from my DVD version with the same frame as it appears in the “restored” version.

From a certain point of view, Lynch’s comments cast into doubt much of what I have written about Inland Empire’s appropriation of the poor image. The version I watched on DVD is not, according to the filmmaker, how the film is “meant” to look; the depthless, un-cinematic image is not “meant” to call attention to itself. Nevertheless, this version of the film, as well as the SD versions previously available to stream, are how many people will have first encountered Inland Empire. I have been discussing the film’s engagement with the poor image as if there is an unproblematic version of “the” film to be discussed, but Lynch’s comments on the remaster bring into focus the reality that the film I saw was itself a poor image. It is here worth returning to Steyerl’s essay and its problematising of the Benjaminian “auratic” artwork and its possible re-emergence in the digital age. For Benjamin, mass reproducibility meant the withering of the aura of the work of art — but for Steyerl, the poor image does possess auratic qualities precisely because its reproducibility is not exact, or even approximate in many cases. Looking for copies of the “same” film online will turn out a hypothetically infinite array of versions depending on image and sound quality, aspect ratio, compression, colour, burnt-in captions; we might find a film, as is often the case to avoid copyright on video-sharing platforms like YouTube, significantly cropped, intentionally pixelated, slowed down, sped up, even flipped so that left becomes right and right left. “By losing its visual substance,” Steyerl writes, the poor image “recovers some of its political punch and creates a new aura around it. This aura is no longer based on the permanence of the “original,” but on the transience of the copy” (42). We have ended, then, where we began — discussing not the film, but my singular experience of that film I watched then.

[i] Exactly why a British secondary school had a set of 18-certificate body horror movies in amongst the obligatory Shakespeare and Dickens adaptations remains a mystery to me.

[ii] Due to the constraints of space, this essay will unfortunately not be able to do justice to the dense sound world Lynch creates in Inland Empire, and therefore sticks to an exploration of its visual components.

[iii] See, for example, Lim and Jerslev.

[iv] As the “rabbits” segments were taken from a webseries (Rabbits) Lynch was producing at the time for www.davidlynch.com, this could be considered as another media form metatextually being engaged.

[v] von Trier’s film followed in the footsteps of Dogme 95 movement in which he was a key player, and which to a large extent had already made viable the possibility for DV-shot films to be shown in cinemas. Interestingly, the plot of Dancer in the Dark concerns a woman going blind, suggesting again the suitability of early DV for probing the limits of vision.

[vi] It is not, of course, that poor images never cross over to “official” media, only that when they appear in mainstream sources like television news, as Steyerl notes, “they are associated with urgency, immediacy, and catastrophe” (45 n.5).

[vii] In the years since the film’s release and Steyerl’s essay—with the rise of social media and especially post-pandemic — real-time screen transmission has arguable become thepredominant mediator of reality for many Americans.

[viii] See, for example, Sterne, “Compression: A Loose History.” Interestingly, in Lee’s Bamboozled, the low-res MiniDV footage represents the film’s “real” world, while 16mm film represents the minstrel shows within the film, as if to suggest, photochemical film = cinema = ideology.

[ix] See Charles Cameron, “Get Back: Why The Beatles Footage Looks So Weird.”

[x] Detailed notes on the process can be found at Janus Films, https://www.janusfilms.com/films/2039.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version).” In The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, edited by Michael W. Jennings et al., Harvard University Press: 2008, pp. 19–55, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1nzfgns.6. Accessed 5 May 2022.

Cameron, Charles. “Get Back: Why The Beatles Footage Looks So Weird.” ScreenRant, 25 Nov. 2021, https://screenrant.com/get-back-beatles-footage-weird-hd-grain. Accessed 4 May 2022.

Dawtrey, Adam. “Lynch invades an ‘Empire’.” Variety, 11 May 2005, https://variety.com/2005/film/markets-festivals/lynch-invades-an-empire-1117922566. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Denson, Shane. Discorrelated Images. Duke University Press, 2020.

Espinosa, Julio García. “For an imperfect cinema.” Translated by Julianne Burton, Jump Cut, no. 20, 1979, pp. 24-26.

Hemphill, Jim. “David Lynch on Restoring ‘Inland Empire’ and Laura Dern’s Oscar Snub.” IndieWire, 13 Apr. 2022, https://www.indiewire.com/2022/04/david-lynch-inland-empire-laura-dern-1234716407. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Hilderbrand, Lucas. Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright. Duke University Press, 2009.

Janus Films. “Remastering Note.” Janus Films, 2022, https://www.janusfilms.com/films/2039. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Jerslev, Anne. “The post-perspectival: screens and time in David Lynch's Inland Empire.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 4, no. 1, 2012, DOI: 10.3402/jac.v4i0.17298. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Lim, Dennis. “David Lynch Goes Digital: Why Inland Empire is better on your TV than it was on the big screen.” SLATE, 23 Aug. 2007, http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/dvdextras/2007/08/david_lynch_goes_digital.html.

Lynch, David. Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. 10th anniversary ed., TarcherPerigee, 2016.

Lynch, David, director.Inland Empire. StudioCanal, 2006.

Marks, Laura. Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Mulvey, Laura. “A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai): from After to Before the Photograph.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, 2007, pp.27-37.

Simon, Brent. “David Lynch on remastering Inland Empire, revisiting his earlier work and the chances of a Dune do-over.” AV Club, 14 Apr. 2022, https://www.avclub.com/david-lynch-inland-empire-interview-dune-restoration-1848795394. Accessed 5 May 2022.

Solanas, Fernando and Octavio Getino. “Towards a Third Cinema.” In Movies and Methods. An Anthology, edited by Bill Nichols, University of Arizona Press, 1976, pp. 44–64. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Compression: A Loose History.” In Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, edited by Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, University of Illinois Press, 2015, pp. 31-52.

Steyerl, Hito. The Wretched of the Screen. Sternberg Press, 2012.

Taubin, Amy. “The Big Rupture.” Film Comment, vol. 43, no. 1, 2007, pp. 54–59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43754496. Accessed 2 May 2022.