The Tragedy of Macbeth

A few years ago, I was lucky enough to see the immersive theatre production Sleep No More in New York. During this film-noir-influenced adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, audience members are free to roam the floors of the vast “McKittrick Hotel” and follow characters on their intersecting pathways that unfold in real time; over the course of the three-hour evening, the play repeats three times so as to allow the audience to see more of the action. Catching glimpses of the same scenes again and again, I was suddenly struck by the suggestion that the meta-tragedy of Macbeth is that its characters are doomed to perpetually re-live their miserable fates, if caught in a nightmarish time loop.

Watching The Tragedy of Macbeth, Joel Coen’s first outing as a director without his brother Ethan, I found it hard to shake the feeling that we’re also trapped in Macbeth’s time loop. If the plot — an ambitious Scottish general fulfils an awful prophecy to become king — hardly needs reciting, it’s probably because it’s been done to death. Cinema has seen its fair share of Macbeths; Justin Kurzel had a stab in 2015, and Coen also follows in the enormous footsteps of Orson Welles (1948), Akira Kurosawa (1957), Roman Polanski (1971) and Béla Tarr (1982). And there’s always a high-profile Macbeth on stage somewhere — London has just had a version with James McArdle and Saoirse Ronan as the murderous Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, and next year New York will see Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga take on the roles.

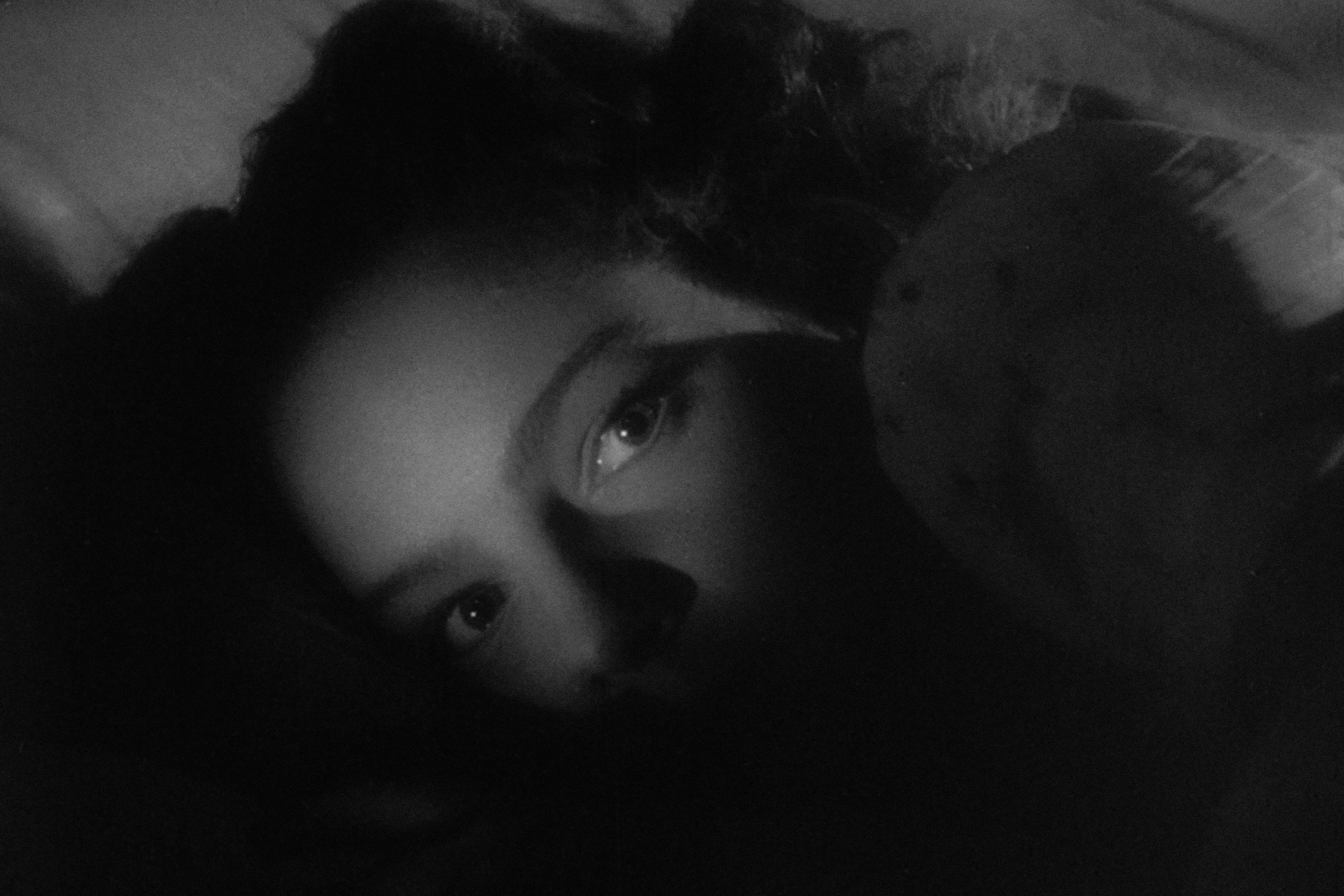

Why make another Macbeth? On paper, it seems as if the play’s themes of fate and chance wrapped in dark absurdity — Macbeth ultimately gets nailed on a linguistic loophole! — is prime Coen Brothers’ material. In fact, Joel Coen’s answer is largely aesthetic. Stefan Dechant’s oppressively angular production design and Bruno Delbonnel’s austere black-and-white cinematography combine to create something beautiful and eerie — all harsh light and dim shadow, evoking some of the masterpieces of German Expressionism. Its stage-like settings seem cut off from any sense of a wider world, an effect emphasised by the tight 1.19:1 aspect ratio further boxing in its characters. Rounded off with a moody score by regular collaborator Carter Burwell, it’s all rather impressive.

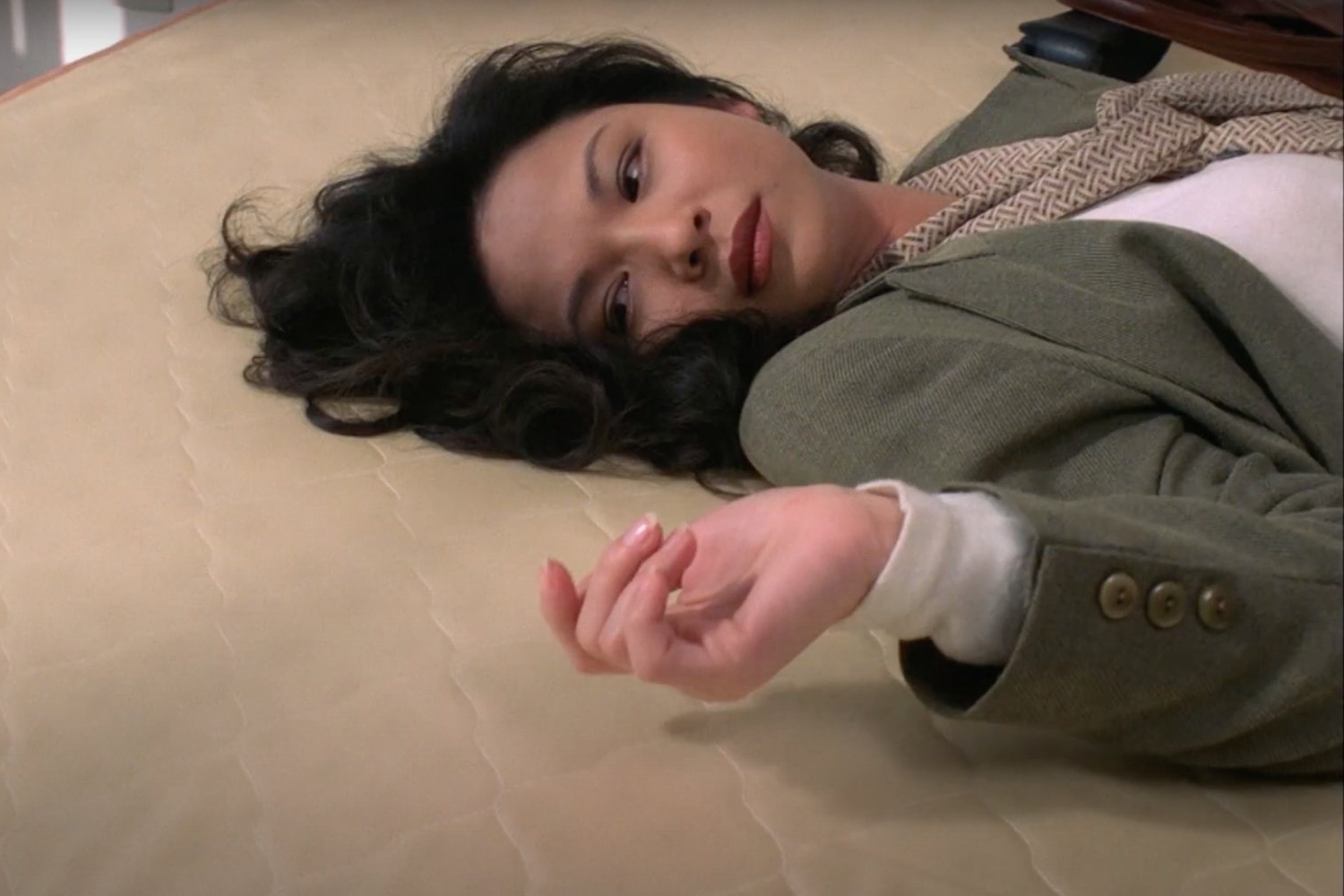

It’s also rather chilly filmmaking, sometimes to the film’s detriment. Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand bring the sophistication you’d expect to the lead roles — it’s hard to imagine either actor delivering anything approaching a bad performance — but there are only glimpses of the passion and intensity that the play bursts with. Put another way, neither actor convinces us they want power as much as Shakespeare’s verse suggests; rather than implying psychological nuance, the effect is a blunting of the material.

Much more invigorating is the supporting cast: Corey Hawkins and Moses Ingram as the Macduffs; Harry Melling as young Malcolm; Stephen Root as the Porter, delivering a single scene of much-needed comic relief; and Kathryn Hunter, playing all three of the Weird Sisters with astonishing physicality. Best of all is Alex Hassell as the skulking Ross, usually a relatively small role expanded here into something altogether more surprising — and menacing. It’s one of the few instances where Coen seems compelled to adapt the play, rather than merely dress it up in (admittedly striking) visuals. All in all, it’s another solid Macbeth that lacks a certain bite necessary to convince those of us growing weary of the play.