Interview: Michael Pearce

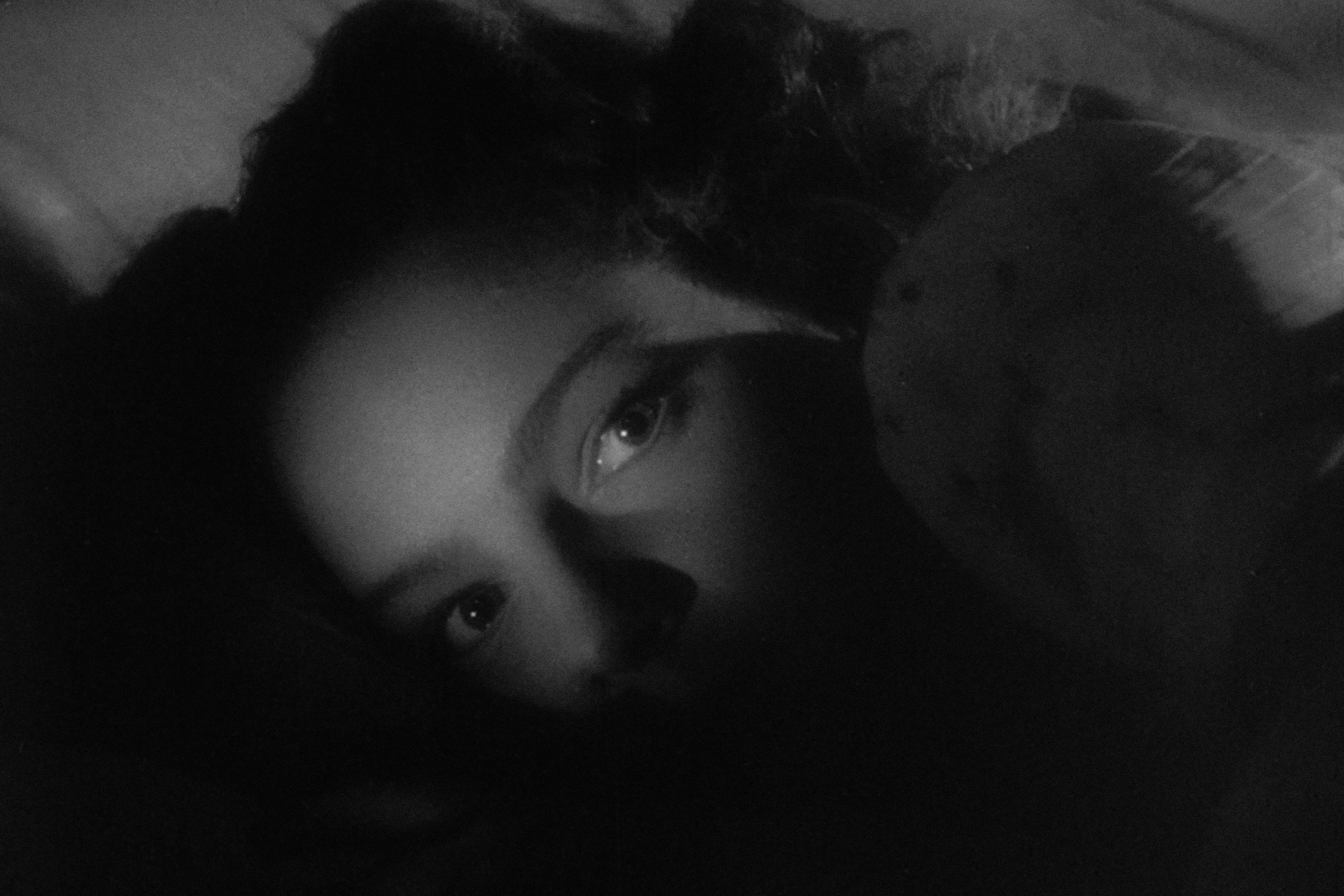

In her comfortable Jersey home with her birthday party about to begin, 27-year-old Moll (Jessie Buckley) rehearses the fakest of smiles in the mirror – the first indication of Beast’s preoccupation with the masks its characters wear. Home schooled after a violent incident as a teenager and still kept on a tight leash by her domineering mother Hilary (Geraldine James), Moll is yet to properly venture into the world. Until, that is, she meets enigmatic outsider Pascal (Johnny Flynn). Handsome and with a certain roughness that ruffles Moll’s snobbish family, Pascal totally beguiles Moll, and soon the pair begin a passionate affair that finally allows her a chance to breathe. But with a serial killer stalking the island and Pascal heading up a list of suspects, Moll finds herself defending him against her family and the police – all the while fighting her own dark past.

Beast, the debut feature of writer-director Michael Pearce, takes its title from the Beast of Jersey, the name given to the notorious real-life sex offender who terrorised Jersey between 1960 and 1971. But, despite a set-up that suggests a straightforward entry into the overstuffed crime genre, Pearce eschews clichés in favour of something altogether more challenging. It’s unclear who exactly the titular Beast is, but there’s a lingering suspicion that the film is asking us to question whether there’s a beast inside us all. Here, Pearce talks to The Student about challenging audiences, learning to embracing genre and the push for a more personal mode of filmmaking.

Theo Rollason: A lot of audience members will come out of Beast feeling unsure what to think in terms of the film’s challenging moral elements – it’s difficult to draw easy lines between good guys and bad guys, right and wrong. Did you always set out to make a morally challenging film?

Michael Pearce: Yeah, I guess, because in some ways the film was a kind of adult fairy tale. And usually in children’s fairy tales there’s quite a clear moral or lesson to be extrapolated from it. I thought that maybe an adult one should throw the audience out more questions, a conundrum. I like that in films generally, where you’re put in a place of jeopardy in terms of your investment in a character; you’re made to feel complicit on their journey, identifying with them, and then that becomes more questionable as the film goes on. I want to take the audience to a place where, near the end of the movie, they’ve been complicit in the character’s journey up until then and it’s too late for them to cash out. I want them to leave with a knot in their stomach, with something to unwrap – they have to do the work, and extrapolate if there’s a lesson. If it’s an adult fairy tale, I want it to be provocative in that way.

Did you ever get worried about alienating the audience by provoking them like that?

I think you have to be close to alienating an audience – there’s a sweet spot when you’re challenging them but they’re still along for the ride. I don’t think you’ll ever do that perfectly with all audience members. I think some audience members will get alienated from this, it will just be too much for them. That’s okay, because if I tried to captivate them other audiences, with stronger stomachs for these types of characters, might have had too much of an easy ride. It depends who you’re aiming for. Hopefully the film’s bandwidth is big enough that a lot of audiences are going to connect and enjoy being in that precarious place where they don’t know whether to keep investing in a character or start to question them. It would be weird if some people weren’t alienated.

It’s ostensibly a serial killer film, but it’s also got a lot going on to do with class, gender, the family unit, race. Even the more traditional crime genre elements have been subverted, or at least skewed in some way. Is that something you were conscious of when writing and directing the film?

Genre used to be a bit of a dirty word for me at film school. I was very much on the arthouse end of the spectrum. Then I started to think about genre a bit more and I realised how it’s actually a really powerful tool. Genre is like a guitar amp – you can still write a very thoughtful folk song with a lot of layers, but genre’s a way to plug in. It’s like going from folk to rock, and it gives you more amplification, it’s more propulsive. The way to mitigate falling into the tropes of genre is that, with each of those tropes or expectations, you just play with them a bit. You either circumvent them, so in this we don’t have the murders of any victims on screen – I don’t know if we need another movie to show us that at the moment. Or then other tropes you try and subvert or twist, like the integration scene. Instead of casting someone that’s a bloke in his mid 50s who’s wearing an anorak and smokes a cigar, it’s a woman who’s acting more like the wise crone in a fairy tale, trying to warn the protagonist from going deeper into the forest. I was just trying to reference some fairy tales as a way to calibrate this away from being a conventional genre film. It’s good to embrace genre as long as you’re aware of what the tropes are.

Towards the beginning of the film Moll can’t seem to fit in with her affluent family, who you get the feeling are more concerned with their appearance in the Jersey community than anything else. Do these ideas have a seed in your own Jersey upbringing?

My family’s very, very different to that [laughs]. When I was a kid I remember going into some friends’ houses and they were more from the affluent parts of the island, and I remember being kind of jealous as a kid of these nicer houses. They weren’t mansions, but they seemed established middle class. But then sometimes I would notice that the family dynamic was very different; there was more of a specific hierarchy in the family, and my friends – I must have been 10 or 11 – would have quite a deferential relationship to their parents. That was very different to my family, where we were all on the same level. I actually found it a bit scary that you would have to look up to your parents in that way, and I realised that I wasn’t jealous of these bigger houses. It depends what’s going on inside the house, the relationships are what’s important. I think that stuck with me. The film is a lot about facades and masks: an island that seems really perfect, but actually there’s these crimes going on; a house and family that seems really benign and wholesome, but is quite dysfunctional; a guy that might be Prince Charming, or might be the Big Bad Wolf; a protagonist who seems relatively innocent, but might have her own dark past. It was trying to find different ways to have that theme resonate through the film.

It extends to Moll’s mother Hilary – she seems like a friendly socialite, but really she’s very controlling of her daughter. How do you write a character like that, one that is manipulative but so nuanced in the way she carries out that manipulation?

Often, I’m quite focused on getting a story structure when I write. I want to see that the acts are there, and where the climaxes will be, the middle point. I quite enjoy the classical structure, and so the characters are often quite archetypal at the beginning. The next stage is to excavate those characters, and try and reveal other layers. In some ways, Hilary is the antagonist of the movie for the first three quarters – it’s a prison break film and Pascal’s trying to help Moll break free from this prison. But then it was like, how do we make her not just one-dimensionally villainous? Maybe there’s charm to her, maybe she’s quite witty. Geraldine [James] is quite elegant as a person. We wanted the audience to understand why Moll would be trapped in that relationship. If it was just explicitly abusive, you might just be screaming at the character ‘why are you still in this relationship?’ When Hilary says to Moll “we’re best friends”, you can understand how – almost like people can be to their pets – she treats Moll harshly to try and domesticate her, as if Moll were a wild animal and she has to constantly be put down to be trained in a certain way.

There’s a lot going on in the script, but it’s also a very sensory film – the farm mud, the crashing waves, and the way you’ve shot Jersey more generally. How did you bring that all together?

Films of the subject matter can be quite procedural: they’re about accumulating evidence. Even the best examples that I love, like David Fincher films, sometimes have a coldness to them. It’s almost like the films are made as a piece of detective work. Again, just as a reaction to what’s gone before, I thought maybe it’s better that this film is more about primal feelings. For that to be reflected in the landscape, the landscape should be elemental in a way. That helped feed into it being an elemental love story. It’s a first love for Moll and it should feel like a burst of feeling. Setting it on some rugged cliffs or having the couple dancing amongst the waves or having sex in the forest –that rush of primal emotions – that seemed like a better canvas for a first love to be happening on. We also wanted it to feel enchanting. A lot of British thrillers of horror films can be very dark and grey and gloomy. I prefer how enchanting and lush a film like Badlands (1973) is, or Wild at Heart (1990). I had more Americana references than I did British references.

I definitely detected the Badlands influence with the dysfunctional runaway couple, and another one I thought might be there was Thomas Vinterberg’s The Hunt, in the scenes that show a community driven by suspicion and paranoia. Do you consciously think about influences when making a film?

Every day I watch a movie. I think it’s actually quite fashionable for directors to say that they don’t have any references or any influences, and they only looked at nineteenth century impressionist paintings. I don’t know whether that’s always sincere, because most filmmakers I talk to are constantly watching movies. I’m so passionate about films, I love the way they communicate. I always think if your references are quite broad and wide, and you’re not zoning in on just one or two movies – you’re loving the atmosphere of one film, the texture of another, the tone of something else – sometimes the references can be quite oblique. A reference I sent to Johnny was Chris Cooper’s performance in Adaptation (2002), because he’s someone that’s quite eccentric and abrasive, but also he’s a very soulful character. I also sent him interviews, just normal interviews, with Ben Mendelsohn, because I find him such a reverent, funny guy; but he’s a bit of a rascal, and you can tell there’s thoughtfulness to him as well. So it wouldn’t just be looking at references. For example, I never told Johnny to look at Kit from Badlands. Because I know the DP loves the film, Badlands would always be a reference inevitably. We were trying to avoid things that were too on point, but I like the tone and texture that American cinema has, it can sometimes be a more seductive film universe to be in. I liked that Beast could be seductive, because it’s going to be challenging later – it needed to be an enchanting story world because we’re going to throw obstacles at the audience as well.

You mentioned America, where a lot of contemporary British directors have turned for their latest features, including Andrea Arnold, Ben Wheatley, Edgar Wright and most recently Lynne Ramsay. Are your sights set on the States?

It’s really story-dependent. I’d love to shoot out there, and to work with places like Texas – it’s like three times the size of the UK, you can take guns into a bank, and those landscapes can be so beautiful and so hostile. In some ways, I’ve grown up with American cinema more than British cinema. It’s in my cinematic DNA, so I’m drawn to those landscapes. I’m attached to something that’s set in New York, and it’s trouble to shoot there because it’s been done a million times – how do you do that differently? I’d like to work on both sides of the Atlantic. I’m not going to move out there any time in the near future, but I love the US style of acting – Stella Adler, Brando, that whole generation of the ’70s of Duvall and Hackman and Pacino, actors like Joaquin Phoenix now – I really love the internalisation of that type of performance. Sometimes British acting can be quite theatrical, and big, and maybe I’m a tiny bit resistant to that.

When your film premiered last year, there was a lot of talk about a ‘move to the country’ within British filmmaking, with rural-set films across genres doing particularly well, like The Levelling (2016), God’s Own Country (2017), Dark River (2017) and to an extent Lady Macbeth (2016). Do you think there’s something worth talking about there, and do you see your film as part of that?

I know film journalists inevitably try and create links… I got to know some of these filmmakers quite recently – we didn’t know each other when we were writing these films and we weren’t all saying, ‘should we all write films set in the countryside’. In a good way, I don’t think Britain wants rip-offs, bland genre films that just reference other movies. Maybe there is incentive to go back to one’s roots, or to respond to a landscape that means something to you, and that has trickled down. The same way that Rungano [Nyoni] made I Am Not a Witch (2017) in Zambia, there’s been a lot of people returning to places they’re from or have a connection to. But that could equally be a filmmaker from London who makes something set in, hopefully, a part of London that we haven’t seen on screen before. So I don’t think it’s a rural-urban dichotomy. But it can only be a healthy thing, a push for filmmakers to make things that mean something to them on a personal level, even if that is within some genre, or it’s a period film. It’s almost like the more specific a texture is, and the more specific the location, the more universal it becomes. Maybe there have been a few films five years previous that were copycat versions of generic American crime thrillers, and maybe some of us are reacting to some of those films that we didn’t respond to.